RESEARCH

Light emitting diodes

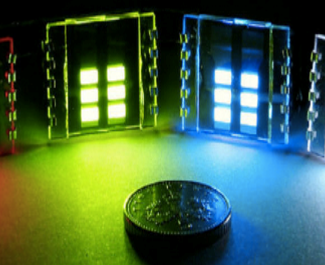

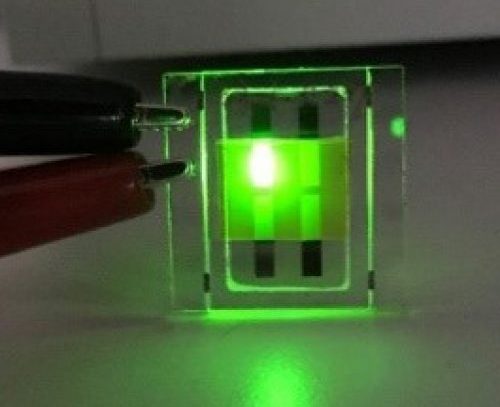

An organic light-emitting diode (OLED or organic LED), also known as organic electroluminescent (organic EL) diode, is a light-emitting diode (LED) in which the emissive electroluminescent layer is a film of organic compound that emits light in response to an electric current. This organic layer is situated between two electrodes; typically, at least one of these electrodes is transparent. There are two main families of OLED: those based on small molecules and those employing polymers. Adding mobile ions to an OLED creates a light-emitting electrochemical cell (LEC) which has a slightly different mode of operation. An OLED display can be driven with a passive-matrix (PMOLED) or active-matrix (AMOLED) control scheme. In the PMOLED scheme, each row (and line) in the display is controlled sequentially, one by one, whereas AMOLED control uses a thin-film transistor (TFT) backplane to directly access and switch each individual pixel on or off, allowing for higher resolution and larger display sizes. OLED is fundamentally different from LED which is based on a p-n diode structure. In LEDs doping is used to create p- and n- regions by changing the conductivity of the host semiconductor. OLEDs do not employ a p-n structure. Doping of OLEDs is used to increase radiative efficiency by direct modification of the quantum-mechanical optical recombination rate. Doping is additionally used to determine the wavelength of photon emission.

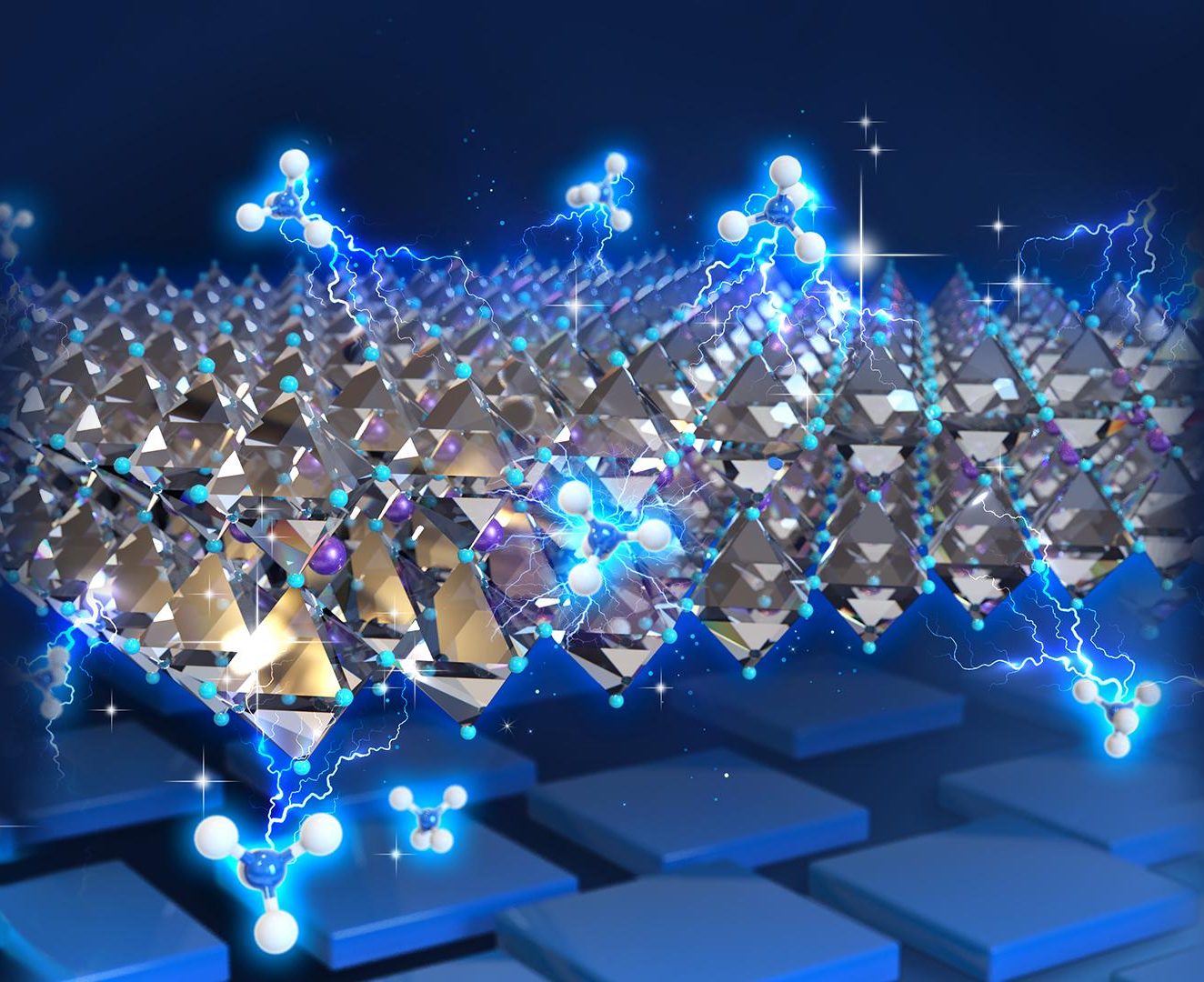

A typical OLED is composed of a layer of organic materials situated between two electrodes, the anode and cathode, all deposited on a substrate. The organic molecules are electrically conductive as a result of delocalization of pi electrons caused by conjugation over part or all of the molecule. These materials have conductivity levels ranging from insulators to conductors, and are therefore considered organic semiconductors. The highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) of organic semiconductors are analogous to the valence and conduction bands of inorganic semiconductors. Most basic polymer OLEDs consisted of a single organic layer. However multilayer OLEDs can be fabricated with two or more layers in order to improve device efficiency. As well as conductive properties, different materials may be chosen to aid charge injection at electrodes by providing a more gradual electronic profile, or block a charge from reaching the opposite electrode and being wasted. Many modern OLEDs incorporate a simple bilayer structure, consisting of a conductive layer and an emissive layer. Developments in OLED architecture in 2011 improved quantum efficiency (up to 19%) by using a graded heterojunction. In the graded heterojunction architecture, the composition of hole and electron-transport materials varies continuously within the emissive layer with a dopant emitter. The graded heterojunction architecture combines the benefits of both conventional architectures by improving charge injection while simultaneously balancing charge transport within the emissive region.

During operation, a voltage is applied across the OLED such that the anode is positive with respect to the cathode. Anodes are picked based upon the quality of their optical transparency, electrical conductivity, and chemical stability. A current of electrons flows through the device from cathode to anode, as electrons are injected into the LUMO of the organic layer at the cathode and withdrawn from the HOMO at the anode. This latter process may also be described as the injection of electron holes into the HOMO. Electrostatic forces bring the electrons and the holes towards each other and they recombine forming an exciton, a bound state of the electron and hole. This happens closer to the electron-transport layer part of the emissive layer, because in organic semiconductors holes are generally more mobile than electrons. The decay of this excited state results in a relaxation of the energy levels of the electron, accompanied by emission of radiation whose frequency is in the visible region. The frequency of this radiation depends on the band gap of the material, in this case the difference in energy between the HOMO and LUMO.